Last week I met Robert Crayfourd, a fund manager at CQS, which has recently been acquired by the much larger Manulife Group. Rob is one of the managers of Geiger Counter Limited, the UK investment company focused on mining assets in the uranium sector, though he also co-managers GPM, which focuses on junior gold miners and a more general natural resources fund, CQS Natural Resources Growth and Income (CYN).

I was put into contact with Rob through Ian Reeves, the Chair of GCL, who also chaired the board at GCP Infrastructure Investments, where I was an NED. I’ve held shares in GCL for a few years and was a little frustrated about the discount there. Ian suggested I meet the manager, and Rob was available to meet at short notice. It is important for private investors to realise that many managers are happy to meet them. We are an increasingly important part of the investment universe, though I understand it can feel a little awkward unless you have that introduction.

Rob gave me over an hour of his time, and although the conversation was never less than interesting, much of it will be familiar to those who believe in the uranium story, or understand the difficulties that the investment trust sector in general has faced over the last year.

However, there were a few matters which Rob highlighted which I had overlooked. It is probably easiest to split the matters discussed into 2: the uranium sector in general and then how GCL has performed. A lot of what follows is my waffle, rather than Rob’s views, and if you already know the arguments for uranium, feel free to skip the next section.

The Uranium Sector

Many others have set out the structural tailwinds behind the uranium sector. The key attraction is that nuclear power relies on uranium and produces huge amounts of energy from a relatively small physical footprint, creating no harmful emissions and only tiny quantities of radioactive waste. It is the safest and cleanest form of energy available and has none of the intermittency problems that bedevil most renewable energies.

As a result, countries are increasingly seeing nuclear as a vital part of the transition to a net zero future. But what makes nuclear unique, from an investment perspective, is that, unlike coal, gas or oil, the price of nuclear fuel is only a small proportion of the cost of nuclear energy.

Nobody knows how much Sizewell C, the nuclear station currently under construction, will cost to complete, but current estimates are in the region of £22-26bn. That is a huge amount of money. In return, Sizewell will produce enough power to supply 6m homes for around 60 years. Over that time, it expects to use around 3,900 tonnes of uranium, or around 60 tonnes per year.

With around 2,200lbs to the tonne, and uranium currently around the $100/lb level, those 60 tonnes a year cost around $13m, or a little over £10m annually. The important point here is that if anybody goes to the trouble of spending £20bn+ to provide zero emission energy for 60 years, they are not going to turn that power station off if the fuel costs rise from £10m to £20m, £30m, or even £100m. Demand for uranium is incredibly, probably uniquely, price insensitive. Once the demand is created, it has no choice but to find supply.

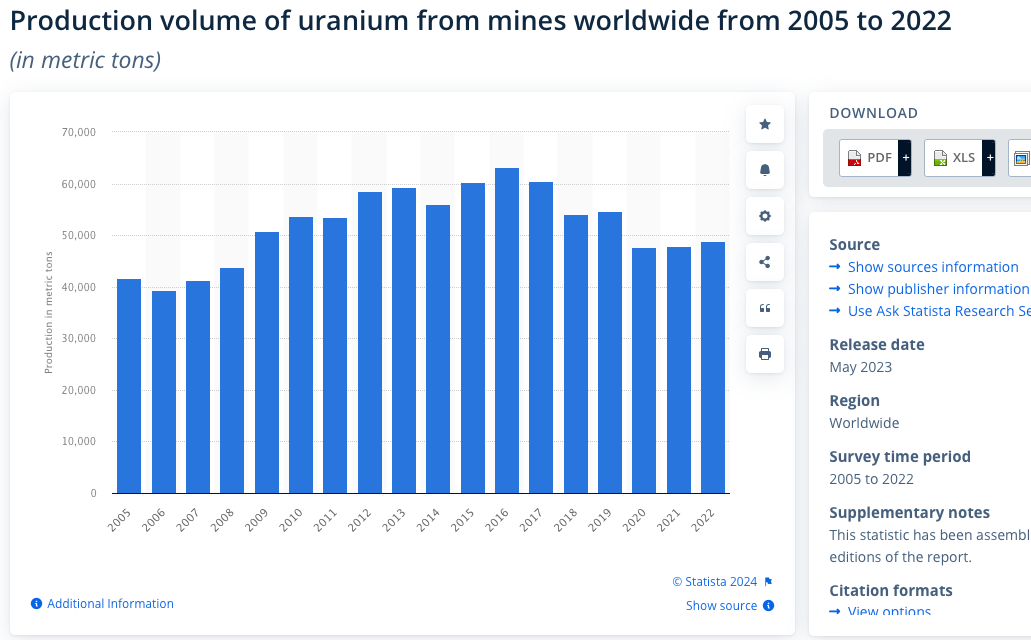

As with the whole natural resource sector, uranium mining has suffered a long period of under investment. It is a paradox of capitalism that in a decade where the cost of capital was very low, little investment went into these capital intensive industries. As a result, uranium production is well down from its peak in 2016.

And again, in common with the whole natural resource sector, bringing new projects into production is seldom straightforward. Finding, proving up, funding, permitting and constructing new facilities often takes well over a decade. Though Rob commented that outside of tier 1 jurisdictions timescales can be shorter.

And while we are doing a quick run through of the world of uranium, it is worth highlighting where the metal is produced. Everyone can form their own view, but it is fair to say that a lot of uranium is produced in areas that pose geopolitical risks.

On the demand side, Russia, Europe and the USA each currently produce a little under 100GW from nuclear power. However, China is targeting an increase from 50GW in 2020 to 200GW by 2030, and India is also planning to double its nuclear capacity. Japan and Europe are also planning to increase nuclear capacity.

Something that I had not appreciated, which Rob highlighted, was the role that small modular nuclear reactors might play. There are many competitors in the nuclear space, among them Rolls Royce. The particular attraction of small nuclear is for AI and power hungry data processing. SMRs have huge advantages for such facilities, and also take the burden off a centralised grid. Any growth in the rollout of SMRs will add to the demand side of the uranium equation.

It is easy to go crazy when looking at the uranium sector, but however you cut it, demand is growing much faster than supply, demand is price insensitive, and much of the existing supply is in jurisdictions that you might be reluctant to be solely dependant upon.

There are other factors which may be negative or have unknown effects on the uranium price. The first is that there was a long period of historic overproduction of uranium. That both contributed to a significant amount of secondary supply (often stockpiles or used fuel which can be re-enriched and used again), and led to some significant resources such as Cameco’s McArthur Lake to be mothballed. Even so, analysts predict that while supply will almost meet demand until the end of this decade, a wide gap starts developing by 2030, with a deficit of around 100M of U308 equivalent lbs pa by 2040. That is around half of the current annual supply.

The other complexity has been the rise of entities like Sprott Physical Uranium and Yellowstone (YCA). These are companies that are simply buying and holding physical uranium. What will they do? If the price of uranium rises, will they sell into the market, or will they attract more investors and buy more? Would they be permitted to hold stockpiles of uranium if there was a real shortage? We don’t know the answers there.

What we do know is that nuclear has a crucial role to play in meeting net zero ambitions, that all of the world’s leading economies are committed to building more nuclear capacity, that once you build it, you have to use it, and that there is no current sign of supply being able to grow to meet that increased demand. Which is why it is such an exciting sector.

A nuclear power station generally lasts a long time – 60 years is increasingly the standard life. The challenge is to secure uranium for the life of the station. That again poses an interesting dynamic. The spot market for uranium is pretty limited, so you want to secure supply well in advance. Of course, it takes a long time to build a power station, so you don’t want to buy it too early, but is a lot of game theory at play here when deficits are forecast in the future and many power producers know they will need uranium in the future.

And finally, uranium has been very volatile historically. From under $10 in 1973 to over $40 in 1973, a slow drift down back to single figures in 2001, before roaring up to nearly $140 in 2007, crashing back down to $20 in 2017, and now back up around $100. Nuclear power has swung in and out of fashion over the decades, but now it seems to be back in favour, the question may be how long the bull market can last and how far can it go?

What about Geiger Counter?

That’s enough about the background. What initially prompted me to ask for this meeting was a frustration at the wide discount that has opened up over the last 18 months at GCL. GCL has historically traded very close to NAV, and sometimes even at a premium, but recently that has changed.

Rob and I discussed some of the issues, which are common across the investment company space. The combination of the absurd cost disclosure rules and the merger wealth managers mean that many investment trusts are now too small to get on the buy lists of the bigger merged entities. The industry has worked hard to get the FCA to engage with this issue, but progress has been painfully slow and a general election will delay the desperately needed reform still further.

I raised my view that specialist funds like GCL are also faced a new challenge from ETFs. A number of these have been launched in recent years, and in theory they offer greater liquidity than GCL. Finally, Yellowcake is a relatively new listed company, and why it only holds physical uranium, it provides an alternative to investors seeking uranium exposure.

Rob didn’t disagree with any of that, but made several arguments that made sense to me. Probably the key one is that GCL has an excellent longer term record.

Expand the timeframe and you can see that the NAV of GCL has risen from a nadir of 12p to around 75p over the last 5 years. While the share price currently languishes around 53p, the NAV is very close to all time highs. It is not the performance that has been frustrating, but the relatively recent phenomena of that wide discount.

Rob suggested a couple of reasons for this. GCL has a relatively unusual subscription mechanism. In rough terms, if you hold shares at the end of March in any year, then you get the right to acquire at the end of April 1 share for every 5 that you owned at the end of March at the NAV of the shares the previous May. Got that?

If the uranium market is quiet, then these rights are often worthless. But last year was a good year for the sector, and so this year, when the shares were trading in March at around 55-60p, holders were given the opportunity to buy 1 share for every 5 that they held, at a price of 37.7p (the NAV in May 2023). It would be rude not to. However, Rob felt that this may have caused some trading, as people used the subscription rights as an opportunity to reduce the cost of their shareholding, rather than increase the number of shares they held. That was what I did, selling a few thousand shares at 52-55p, and then buying them back at 37.7p.

A related issue is the strength of the share price over the last 5 years. Anyone who invested in the dark days of 2019/2020 has probably seen their holding grow to a large proportion of their portfolio. Coupled with the subscription option, it is natural to see some selling.

As far as reducing the discount to NAV is concerned, Rob emphasised that any decision to buyback shares was for the board, and there have been recent buybacks. However, although the mathematics works for long term holders, it feels odd to see a company issue subscription shares at 37.7p and then buy back shares a few weeks later at 52/53p.

And while the discount is frustrating, it can equally be seen as an opportunity. Currently the NAV is around 72 and the share price 53, so the discount is over 20%. It is difficult to see that widening much. Whether it will ever close to the degree that GCL again trades at a premium is questionable, but as long as it doesn’t get worse, investors are no worse off. I regard it as an irritation that only offers upside for anyone buying or holding from here.

As far as ETFs are concerned, they do offer cheaper access to the uranium market, and usually offer better liquidity than GCL. The problem is that narrow focus ETFs have never really been tested in the market.

The structure of ETFs is worth briefly understanding. In short, the ETF sponsor creates units in pre-determined block sizes (say 50,000 units at a time), and these are available for purchasers to buy. The subscription monies are paid to an Authorised Participant (AP) who goes and buys shares in the actual underlying securities in the market. The same process can happen in reverse, when investors sell ETFs. However, the big unknown is what happens in the event of a major sell off. Would the AP be able to find purchasers? If too many people use ETFs to access the market, where will the discretionary buyers be who mop up those sales?

This diagram shows how ETFs work. From Ultimasfundsolutions.com

These can be dismissed as theoretical arguments, and it is true that ETFs have not in practice experienced this problem yet. However, most ETFs have historically been big index trackers. Specialist ETFs in smaller markets are to some degree untested. And as well as the liquidity risk, while APs are invariably global financial institutions with household names, the events of 2008 showed that even the biggest global banks do pose some counterparty risks.

Investment companies, for all the frustrations with liquidity and discounts, do provide permanent capital that managers can use to build up a portfolio of long term positions. They own the underlying securities in their own name. The team at GCL have done, building a concentrated folio, largely focused on North American companies, that looks quite different from the benchmark. The current bias is towards developers, which are currently at attractive valuations.

When you compare GCLs portfolio against the Uranium X and Han/Sprott ETF, a few facts jump out: firstly, it is much more concentrated, with the top 5 holdings representing over 60% of the assets; secondly, that it has little exposure to physical uranium as an asset class in itself; and lastly, it has much lowed exposure to the sector bellwether Cameco than the ETFs.

Cameco is itself a fascinating company. It has entered into lots of forward contracts with various caps and floors on the price it will receive for uranium. The upshot of this is that, for several years, Cameco will not benefit materially from the upside in uranium prices. In 2027, for example, if uranium rose in price to $140/lb, they would received $76/lb for their production. On the upside, if the price collapsed to $20/lb, they would receive $37/lb. However, the point is that the sector can have nuances that it is hard for the casual investor to fully understand when buying individual companies.

Geiger Counter top 5 holdings:

Clearly, a lot is riding on NexGen, which is a pre-production Canadian miner with an AISC of around $10/lb and full exposure to any uranium upside. Once they are in production they expect to be in the largest 10 resource companies worldwide measured by free cash flow, and to be producing over 50% of the western supply of uranium. However, although they have Government and Indigenous Nations support, they have yet to receive full permitting approval. There is also significant exploration upside, but the risk profile of any pre-revenue miner and the accompanying volatility in their share price can be dizzying. Their recent corporate presentation is well worth a read (https://s28.q4cdn.com/891672792/files/doc_downloads/2024/06/NXE_CorpDeck_June-2024.pdf).

UR-Energy has a market cap of under $500m, and doesn’t turn up in anyone else’s top 10 list. It is a fully permitted company with US based assets with infrastructure already in place to increase production and off take sales to the US Department of Energy.

By contrast, here is the Global X Uranium ETF top 10 holdings:

Han Sprott etf top 10 holdings (and remember, Sprott also has a physical Uranium ETF):

I really know nothing about any of these companies. I can look at Black Rock World Mining (BRWM) and have a view – albeit a superficial one – about whether I want more copper exposure than iron, or if I think Rio Tinto is a better bet than Glencore. I can compare Scottish Mortgage (SMT) to Fundsmith and I’ll know what most of the companies do. But the uranium sector is clearly very specialist.

Ultimately you have to decide whether you back the managers to find the best opportunities. GCL will ultimately be judged on whether its high conviction asset selection beats the sector as a whole. With the top 3 holdings representing 40% of the fund’s assets, I would hope that focus reflects a confidence in their highest conviction choices. They don’t need to make such big bets, after all. And for what it’s worth, I want investment trusts to have conviction. If I just want to track a market or sector, there are plenty of choices. I want investment managers to do the research, have conviction and add value.

To make that judgment on GCL, although past performance is no guide to the future etc, it is all we have. And the past performance of GCL very much depends, as the analysis of the discount does, upon the timescale you choose.

A lot of the Uranium ETFs are relatively recent launches, and so to go back you have to compare GCL to the VanEck Uranium and Nuclear ETF. And over 5 years, GCL has outperformed by quite a margin, albeit with much more volatility.

However, if you add in the Sprott ETF and Yellowcake (YCA) and look at performance since the Sprott launch in 2022, GCL has underperformed significantly. A lot of that underperformance is the result of a discount going from zero to over 20%. And remember, if you took advantage of the subscription rights, your performance would be better than this. Finally, the chart below starts at the moment of the peak in the chart above. If it began 2 months later it would look very different, even before you add in the subscription rights.

Here is the same chart with a start date a few weeks later.

If you have read this far, I assume that you are sold on the wider argument as to why uranium may be an exciting opportunity, and the question is whether GCL is the best way to access the opportunity.

GCL has been an excellent longer term performer. Over the last 2 years it has underperformed new entrants in the uranium market, and this has led to a wide discount appearing.

As an investor, you can look at this as either a sign that the market has changed, and that ETFs are a cheaper, more liquid way to play the sector. Or you could argue that GCL’s concentrated portfolio and excellent longer term track record perhaps make this an opportunity. It is a paradox that while investors get frustrated when investment trusts trade at a discount, that actually means that the shares are on sale. If you can buy investments you want for the long term at a discount, that is always a good thing.

Whether the discount will close, or whether, in light of the enlarged choice in the Uranium space, it becomes permanent, is harder to answer. My instinct is that it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t seem likely that the discount will get much wider, and so at worst, it can be ignored, and at best, it provides an upside opportunity if it narrows.

My best guess is that GCL’s concentrated portfolio will always lead to volatility, and that this may magnify performance, as the discount narrows during upswings and widens during falls. Ultimately, what matters is the ability of the team to pick the right stocks, the performance of the sector, and the period that you are looking to invest for. I came out of meeting confident that Rob knew the sector well, and that it was a sector with a great long term future.

My overall conclusion is that if the uranium thesis plays out, the upside could be very considerable, and be felt over a number of years. So for now, I am tucking away my shares in GCL, and looking to hold them for the very long term. But I’ll be keeping an eye on performance against the ETFs, the discount to NAV, and the regulations around the investment trust sector in general. A lot currently depends upon the performance of NexGen, and you have to trust the managers to understand the risks and opportunities in that regard. If you would prefer a more diversified play, there’s no shortage of alternative choices.